Blog

Tagged In: clearcut, native species, Wayne National Forest, white oak

White Oak: Ohio’s Most Important Tree

Nathan Johnson and Molly Jo Stanley, March 8, 2023

“If oak is the king of trees, as tradition has it, then the white oak, throughout its range, is the king of kings.”

Donald Peattie, A Natural History of Trees of Eastern and Central North America (1991)

“White oak is the standard by which all other oaks are measured. The majesty of a mature tree warrants pause for reflection.”

Michael Dirr, Dirr’s Encyclopedia of Trees and Shrubs (2011)

“White oak (Quercus alba) is an outstanding tree among all trees.”

Burns & Honkala, Silvics of North America. Vol. 2: Hardwoods (1990)

Meet the Main Character of Ohio’s Native Landscape

Should you walk into an oak-hickory forest in Southeastern Ohio, you very well might find yourself breathless in the presence of towering (80+ feet), robust (38+ inch diameter breast-height) trees. You might rest on a fallen giant on the edge of a ridgetop, and marvel at the sight of a ghostly tree with sprawling, gnarled branches and immense knobs along the lower trunk from where branches have shed. If these gnarly trees have a beautiful carpet of green moss on the bottom of their trunks; if they have light gray, plate-like bark that gets shaggier the further up the tree you look; if their leaves have numerous, rounded lobes — well, then you’ve probably found yourself in a white oak grove.

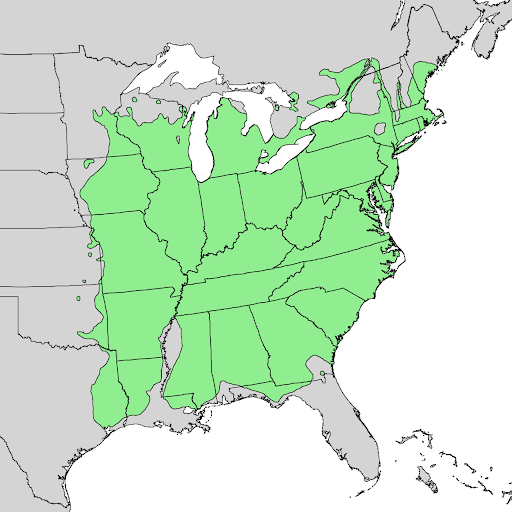

White oak (Quercus alba) is the most important wildlife tree in Ohio and the eastern half of the United States. It also happens to be one of the most beautiful and “charismatic” trees of the eastern forests. And it’s one of the longest living organisms in the eastern United States, commonly living for 300 to 600 years or more. White oak is a true keystone of many forest ecosystems. And, in a twist that seems truly magical, eastern North America’s best tree was once its most numerous. White oaks once dominated much of Ohio’s landscape and the eastern forests.

But that was during Indigenous times, before European colonists and their descendants clearcut the eastern forests. Sadly, heavy timbering uniquely hurts white oaks. Many trees grow back after a cut, but white oaks usually do not. The historically dominant status of white oak eroded substantially with the first waves of industrial clearcutting. With every modern-day clearcut, white oak is further erased from the landscape.

We must protect the white oaks that stand on our public lands. This holds especially true for our state and national forests where commercial logging is often the priority of industry and government agencies. Any temporary benefit of large-scale white oak logging on our public forests is vastly outweighed by the permanent loss of this tree on our landscapes. Our government agencies, and private landowners, need both better incentives and more resources to appropriately steward and protect this special tree.

White Oak Is the “Tree of Life”

Oaks support more forms of life — birds, mammals, insects (including moths and butterflies) — than any other class of tree. It’s not even close. And oak acorns are, at least seasonally, the most important source of sustenance for numerous species, including deer, turkey, grouse, and bear. Oaks are life.

Even among the life-giving oaks, the white oak is truly exceptional. White oak acorns are sweeter and more sought-after than those of many other oaks. The imperiled cerulean warbler prefers white oaks over all other trees for nesting. State-endangered black bears prefer white oak acorns so strongly that their reproductive success in the Appalachians is directly tied to annual white oak acorn production. Many white oaks have unique flakey, plate-like exfoliating bark characteristics that make them ideal endangered Indiana bat habitat. As the longest-lived and most durable of the eastern oaks, Quercus alba can provide ecosystem and habitat stability for centuries. In fact, old white oaks commonly rot from the inside out. But they are so strong that they often remain standing, albeit hollow or filled with cavities, for hundreds and hundreds of years. This makes them perfect homes for wildlife — cozy, protective dens for generation after generation of forest animal.

We Must Speak for These Trees

During Indigenous times, white oak was dominant across much of the eastern forests, accounting for an astounding 40% of the canopy in Southeastern Ohio. But white oaks’ dominant position eroded substantially when the indigenous forest was all but completely cut down from the mid 1800s through the early 1900s. By the early 1990s, white oak made up only about 14% of Southeastern Ohio’s forest canopy. The most recent data from the U.S. Forest Service shows that white oak is in serious decline in Ohio today. This same data shows that unsustainable logging is the most significant driver of white oak’s decline.

Interestingly, Forest Service data shows that there are more than twice as many white oak trees on the Wayne National Forest (per acre) as on surrounding private forest land in the 17 counties of southeastern Ohio. This fact is significant. And it is not random. Clearcutting and extensive commercial timbering have been largely curtailed on the Wayne for the past three decades. Meanwhile, the Forest Service estimates that the majority of private lands surrounding much of the Wayne have been heavily logged during that same time. Hence the disparity in white oak composition.

The unique characteristics and survival strategies of white oak — slow rate of growth, shade tolerance, poor stump sprouting ability at maturity, tendency to cluster in groves, and exceptionally long lifespan — make it a poor competitor in aggressive commercial logging regimes. Faster growing tree species usually replace it if and when a cut-over forest regrows. Simply put, white oaks are not meant to be clearcut or heavily logged. The available scientific evidence suggests that, historically, white oak attained landscape dominance by recruiting in small canopy gaps of approximately 1/20th an acre in size. By contrast, commercial logging operations clear forest to the tune of tens to hundreds of acres at a time.

In addition, the fungal networks that support white oaks and oak-hickory ecosystems are especially sensitive to intensive logging. These fungal connections between and among trees form an essential part of oak ecosystems. They facilitate communities of trees that communicate, share resources, and foster the establishment and growth of young oak seedlings and saplings. When an oak forest is clearcut or heavily logged, these fungal networks are destroyed. Often, they are replaced by competing fungal networks that serve competing tree species and forest ecosystem types. In other words, heavily logging an oak-dominated forest often destroys the entire oak ecosystem. Perhaps one day soon our public land managers will acknowledge and heed this fundamental truth.

Our remnant white oak groves are the most life-giving natural places on Ohio’s landscape. And our public lands are where these special groves remain strongest. These public trees and ecosystems belong to all of us. Many of these white oak trees will still be standing more than half a millennium from now if we grant them the freedom to do so. We can have a real say and hand in their future. But only if we make our voices heard.

Learn to see your oaks. Come to know them. Speak for them. Fight for them. Protect them.